Nau mai, kuhu mai. Welcome.

The ancient story Te Waiatatanga Mai o Te Atua, The Song of the Gods was first written down in 1849 by Matiaha Tiramōrehu. He was a tribal scholar of Ngāi Tahu, the traditional owners of the land that is now Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Tiramōrehu was born at the large papakāinga and trading settlement of Kaiapoi in the early 19th century. After the destruction of the village during intertribal warfare in 1831, Tiramōrehu and many others fled to other parts of the South Island. Tiramōrehu went to Moeraki where he maintained his position as an important political and spiritual leader. The same year Tiramōrehu wrote Te Waiatatanga Mai o Te Atua, he also wrote to the government seeking redress for unfulfilled promises made to Ngāi Tahu by the Crown. This was the beginning of Te Kerēme, the Ngāi Tahu land claim that lasted for seven generations. Tiramōrehu lived in tumultuous times of fighting and change, just like the gods experienced in his origin story.

The story centres on Papatūānuku the earth mother, Raki the sky father, and their children, from whom we all descend.

This is a story that begins in Te Pō, the darkness.

A note on language:

Use of the letter “k” in place of the digraph “ng” is unique to the dialect of Ngāi Tahu, and is especially common in South Canterbury, Otago and Southland. For example, the sky father Raki is known more commonly in the North Island as Rangi. Indeed, Ngāi Tahu frequently refer to themselves as Kāi Tahu.

In his manuscript, Matiaha Tiramōrehu uses the letter “k” and the digraph “ng” interchangeably. However, it is likely that he would have mostly used “k” in everyday speech. As such, “k” is used throughout this exhibition in place of “ng”.

The Artworks

The Story

Matiaha Tiramōrehu, reimagined by Ariana Tikao

Mai i Te Pō ki Te Ao Mārama / From Darkness to Light

We begin in darkness. As in all of our beginnings in our mother’s womb. We float in amniotic fluid, full of potential, Te Kore. Gently rocking waters, like the buoyant currents of Takaroa, god of the sea. Some say Takaroa was Papatūānuku’s first love. After their children were birthed, he journeyed far away to bury the children’s placentas. While he was away Papatūānuku the earth mother fell in love with Raki the sky father. Raki’s mighty expanse of blue was too powerful, his brilliance too beautiful to resist.

We begin in darkness, Te Pō. In the breath shared between our parents. We hear a murmur. Indistinct at first. Turning into a rumble. A low hum. A song. Te waiatataka mai o te atua. The gods singing. The children of Raki and Papa began to sing. They formed the universe as they chanted, intoning the foundations for all future beings. Like a baby vocalising, trying out all the possible sounds of language: gurgles and clicks, highs and lows, squeals.

Kei a Te Pō te tīmatanga mai o te waiatatanga mai o te Atua.

The beginning of the singing of the Atua is with Te Pō (The Night).

As the gods sang, delicate threads of sound wove around each other, building into physicality. Sinews bound the parents together, and the children were living in a dark, confined space between them. After what felt like aeons, they felt a yearning for something new, beyond this cramped existence. They began to talk of ‘what else’. The parents could feel the growing discontent, but they were so tightly bound they were unable to stretch or move to create more space.

Te Weheka / The Separation

So Raki said to his son Tāne: “Son, you must lift me up. Separate me from your mother”. This was the only way to let light enter the world. Raki issued his instruction to Tāne even though he knew he would be injured in the process, or even killed. An act of self-sacrifice. It initiated the change for the gods to move into Te Ao Mārama, the World of Light. Tāne was not so keen at first: “I don’t think I can, Father. How about my older brother Rehua?” Raki insisted that it must be Tāne, but told him that his other siblings could all play a part. They tried stamping down on their mother’s body, gaining purchase with their feet. They heaved and tried to lift Raki, but their father would not budge. Tāne’s younger brother Paia laid down his intention by singing his magical karakia:

Tīkawea a Raki, whakawaha a Papa, whakatikatika tuarā nui o Paia, mamae Te Kawaihuarau

Bear up Raki on your back, carry Papa on your back, straighten great back of Paia, feel pain Te Kawaihuarau

With these words Raki began to rise. Auē! Te mana hoki o te kupu. Such is the power of the spoken word.

Raki and Papatūānuku declared their undying love, weeping for each other. As sinews started to snap, there was a wail of pain. Then an almighty roar as the physical and heavenly elements began to tear apart. Raki’s tears would now rain down on Papatūānuku and be gathered in the morning’s dew. Papatūānuku’s woeful sighs would rise up as mist and gather amongst the clouds that adorned Raki’s body.

Raki continued to be lifted up even higher and Paia’s karakia continued:

Who will provide a prop? Ruatipua

Who will provide a prop? Ruatahito.

An upright post, a sloping post, a fortifying post, an aitutonga.

That prop, then these other props ascend, now our heavens are secure.

Prop the Great Cloud, the long cloud, the thick cloud.

The coming to rest of Rakiriri, gather Rakiora. Listen out.

A deafening shout resounded from above.

Special poles were placed in different positions, angled, straight, and perpendicular, so that the new configuration of heaven and earth would stay apart and be stable and strong. From here on, the gods would need to adjust to their new world. Te Ao Mārama, the World of Light.

Ka kākahuria e Tāne a Raki rāua ko Papa / Tāne Adorns Heaven and Earth

Tāne and his siblings were amazed by the incredible brightness that surrounded them in Te Ao Mārama. They had only known darkness up until now. With the light also came a shift in consciousness. They became aware there was more work to do. More life to create. There were no coverings on either parent; they were both cold and naked. Tāne went about adorning them both. He gathered the rāhuikura, a red ochre paint, to mark the boundaries of their new world. But this kura, red, would not stick to Raki. Tāne kept trying and realised that it could be seen during the daytime; sometimes we still see the beautiful red colour in the sky at dawn and sunset. It could not be seen at night though. Therefore, Tāne sought out stars and constellations from his younger brother Wehinuiamaomao, a weaver, carefully laying them out as star maps, and star waka. These whetū created a foundation for the world of astronomy. People still rely upon these guiding lights in the darkness for seasonal knowledge and signs for navigation whether by sea or on foot.

Tāne received some plants from his older brother Rehua to adorn their mother Papatūānuku. Many different goddesses provided the elements needed to create all of the plants and other creatures that live in the forest. In the third year after planting, the Kahikatea tree bore fruit, then the birds flew down from the heavens, bringing with them songs and the foundation of language. Te Wao Nui a Tāne! The forest of Tāne!

Lastly, Tāne created people, first man and then woman from the earth of Hawaiki. The first man was named Tiki-auaha, and the first woman Io-wahine. From this couple sprung all of the people of the earth, and eventually us. Our job is to be kaitiaki, guardians, who maintain this beautiful world, caring for all that the gods created way back then, in the beginning.

Glossary

Waka – canoe(s)Whetū – star(s)

He Whakamārama / Key Concepts in Te Ao Māori

Whakapapa

Whakapapa is the foundation of the Māori world. It is based on genealogy and gives order to both human and non-human entities. Whakapapa shows how all things are connected. Everything in te taiao, the natural world, has whakapapa: stones, mountains, rivers, stars, as well as plants and animals. Human beings came along later in the sequence of creation. In the origin story shared by Matiaha Tiramōrehu, there is a strong emphasis on lines of descent of the gods, which also speaks of order within nature.

Māori oratory includes reciting whakapapa, the lines of human descent carefully selected to highlight connections relevant for the occasion. Through having a whakapapa relationship with the land and other aspects of nature, we are reminded of our junior status and of our role as kaitiaki, to look after others in this schema of all life. At this time as we face monumental environmental and social challenges, we may look to whakapapa as a blueprint for balance.

Te Maramataka

Marama is the moon. Maramataka is the moon calendar, which helps measure time through the moon’s cycles and seasonally-based knowledge. The Western world is governed by the Gregorian calendar based on the rātaka, or movement of the sun, which starts in January and goes through to December. Māori ancestors developed seasonal knowledge systems over centuries and millennia based on observing environmental cycles unique to this part of the world. The landscape and weather patterns in Te Waipounamu are different to those in the North Island, and so are the plants, birds, fish, and tides that we receive guidance from. In this colder climate, we need to be particularly aware of the seasons and any fluctuations. The maramataka can help us to know when is a good time for fishing, travelling, or when to plant or harvest crops. For those living in cities today, we can convert the knowledge of the maramataka to our modern context of when might be a good time to work hard, or when is a good time for rest. Environmental knowledge and wisdom was paramount for our ancestors’ survival and is still important today in order for us to live in harmony with nature.

Astronomy

Stars and constellations in the night sky contain knowledge and can be a navigational tool, but can also influence our relationship with the environment. Stars are a significant part of Matiaha Tiramōrehu’s creation story. After Raki the sky father and Papatūānuku the earth mother were separated by their children, Tāne and his siblings adorned the night sky with stars which provided a beautiful cloak for their father. Rehua was the eldest son of Raki and Papa in Tiramōrehu’s version of the story, and Rehua is also known as the star Antares, which is particularly associated with the summer months.

The Milky Way is known as Te Ika o Te Raki, the Sky Fish, as it glistens with a shimmery light just like a fish when it is first caught and pulled up out of the water. In Māori culture, when loved ones perish they are said to go back to the stars.

Matariki and the star Puaka are important signallers of the Māori new year in the middle of winter. The nature of their appearance holds information as to what kind of season ahead the people will be entering into.

Observing the night sky and stars was also important to our European ancestors, as the stars and constellations helped order their knowledge systems too. This observatory tower was erected within the original campus of the University of Canterbury in 1896. It collapsed in the February 2011 Canterbury Earthquake but was rebuilt and reopened in 2022. The Observatory atop this tower is used for viewing the stars with a telescope, but the Māori ancestors of this whenua were observing the stars here long before.

Tukua kia tū takitahi kā whetū o te raki

Let each star in the sky shine its own light

Te Taiao

Te Waiatatanga Mai o te Atua, The Song of the Gods, is an immersive, multi-sensory experience that recounts one of Ngāi Tahu’s origin stories. Inside the exhibition you see and hear many elements that are representations of atua, gods who relate to the natural world, and their children. Elements of te taiao, nature, are personified which gives us a very real and immediate connection. We are related to the earth as she is Papatūānuku, and to the sky, Raki.

Ngāi Tahu’s ancestors lived in ways that were very connected to nature, as they journeyed by foot or in waka and sourced their food during seasonal gathering expeditions. Our people traded resources with each other and northern iwi. Ngāi Tahu also held most of the country’s sources of pounamu, a prized stone that was collected on arduous journeys from Te Tai Poutini and worked here into useful tools, adornments, and taonga. We are fortunate to live on and with this beautiful land and it is a huge responsibility for us all to take great care of our natural world for the benefit of future generations.

Mō tātou, ā, mō ka uri a muri ake nei.

For us, and those who follow.

Glossary

Kaitiaki – guardian(s)Te Waipounamu – the South Island

Matariki - the Pleiades star cluster

Puaka – the star Rigel

Whenua – land

Waka – canoe(s)

Iwi – tribe(s)

Pounamu – greenstone / jade

The Tai Poutini – the West Coast of the South Island

Taonga – treasure(s)

Te Waiatatanga

Christine Harvey: Laser cut acrylic.

Te Pō (The Night). Te Ao (The Day. Te Kore (The Void).

Te Mākū (The Damp) coupled with Mahoranuiatea, and Raki (The Sky) was born.

Papatūānuku was not connected with Raki but with Takaroa. She joined with Raki when Takaroa had gone away.

Raki was still clinging to Papatūānuku.

This contemporary kōwhaiwhai design by multi-disciplinary artist Christine Harvey is based on a repeating motif of two looping koru that intersect and encircle in a pūhoro design. Christine is a well-known tā moko expert, one of the people who revived customary tattoo practices and brought it back into the realm of the living. The pūhoro motif is applied within the realm of moko, particularly around the thighs which is one of the very strong areas of the human body. The pūhoro is connected to whakapapa, the genealogical links that bind people and connect all things within te ao Māori. There is a link with this pattern to the creation story, where Raki is injured in these parts of his body when Takaroa attacks him for being Papatūānuku’s new lover. The pūhoro is very much connected to whakapapa, the genealogical links that bind people and connect all things within te ao Māori.

Movement is created in Christine’s design whereby each koru is a source that pushes forth a current, like energy flowing. Design elements converge to create an intensity of frequencies, then reflect as an echo. The visual symbols relate to the balance of creation.

The atua birthed by Papatūānuku: Rehua, Tāne, and their younger brother Paia, elevated Raki into the heavens using props. Other great unions produced offspring who cloaked our world in glorious ways with flora and fauna. These great primordial parents Takaroa and Raki, in their unions with Papatūānuku, gave us our world as we know it.

Glossary

Te ao Māori – the Māori worldAtua – god(s)

Other Artworks

Pou Ruatahito

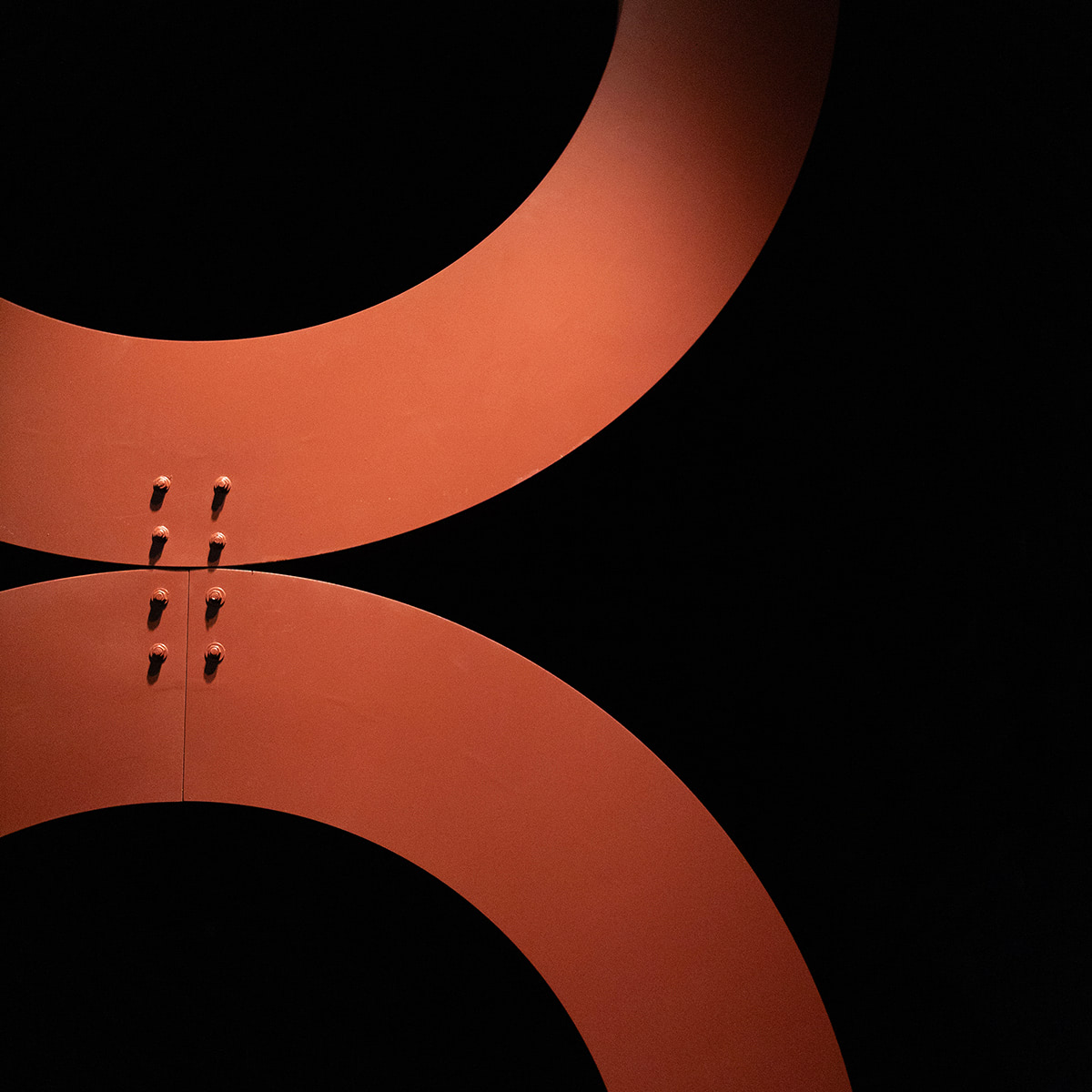

Turumeke Harrington: Painted steel

Prop of whom? Prop of Ruatahito. An upright, a digging stick, a protection, an aitutonga.

Then Tane thought he would create humankind. He fashioned it in Hawaiki, the hands were formed, the head, the feet, the thighs and the whole body.

Turumeke Harrington is an installation artist based in Pōneke Wellington. She has a background in industrial design and fine arts, and a passion for whakapapa, space, colour and material. Turumeke positions her large sculptures and mixed media constructions at the intersection of art and design.

Turumeke’s Pou Ruatahito was created out of steel, expressing strength and the tension created when two like magnets are repulsed by each other. Is Turumeke’s work expressing connection as two curves back-to-back, supporting each other, or are we invited to walk beneath an otherworldly figure? As an abstract form, Ruatahito can mean many different things, like Papatūānuku reaching up for Raki, or Paia bent over, suspending his father Raki on his back. We might also see Papatūānuku, our mother, our whenua, our place to stand who grounds us, holding all who prop up Raki. Perhaps this references the power of women to support and nurture, and who are often the source of strength and unity within a whānau. The red ochre colour of the pou is symbolic of the kurawaka, the sacred earth used by Tāne to create the first woman, Io-Wahine.

Turumeke’s pou can also symbolise the exchange of water as mist rising, and tongues rising and descending. This speaks to the desire and yearning of Raki and Papatūānuku, but also touches upon our own humanity. Although made of metal, a strong, seemingly unbending material, the curves and open form of the pou make it appear very human and bodily.

Glossary

Whakapapa – genealogyWhenua – land

Whānau – family

Pou – post / pole

Other Artworks

Pou Ruatipua

Alex Mcleod: Carved tōtara, enamel paint, pāua shell

Tāne asked his father “How shall we kill you?” Raki said “You will have to lift me up, so that your mother lies separate from me.”

Ruatipua is the name of the support by which Paia propped up Raki.

When the propping of Rakinui was completed, the world was bright as new dawn.

Alex Mcleod has been practising toi whakairo, customary Māori carving, for more than 20 years. Alex chose to carve tōtara wood for his pou, prized for its straight grain and its hardwearing heartwood with relative light weight. Tāne was the son chosen by Raki to separate him from Papatūānuku, to allow light to enter the world. Tāne is known as god of the forest and when you see the tall trees in the ngahere reaching up to the sky, you can imagine these trees as both the link between earth and the heavens, and the props that keep them apart. The tōtara, like all others who dwell in the forest, is a descendant of Tāne. Alex has left the reverse of the pou in its raw state, reminding us of the original form of the tree.

This pou represents the prop Ruatipua in Tiramōrehu’s creation story. Papatūānuku looks serene at the bottom of the pou in her earthly realm. Ruatipua stands above, keeping Papatūānuku apart from Raki and allowing all of the life between them

to prosper. Rūaumoko, the atua of earthquakes who still resides in Papatūānuku’s womb, is shown in the form of a manaia. This references the potential for unrest and shaking of our realities, a warning for us to be ready for change at any time. People are not in control of the natural world and sometimes we need to be reminded of this. However, Papatūānuku continues in her abundance and giving, and we must be ready to reciprocate by caring for mother earth and all in her domain.

On both carved figures, Alex wanted to capture the hei tiki form well known throughout Te Waipounamu, the South Island. You can see these characteristics in the protruding puku, broad shoulders, rolling forearms, legs, forked tongue, and enlarged eyes. The hei tiki form can also symbolise the foetus, which represents fertility and potential. This reminds us that all peoples of the world are descended from Tāne and Io-Wahine, the first woman whom he created.

Above Ruatipua, Alex has carved kōwhaiwhai, scroll-like patterns often seen on the rafter beams inside meeting houses, and geometric tāniko motifs often applied to the boarder of cloaks. These represent the light and life let into the world by Papatūānuku and Raki’s separation, as well as the strength and stability of both their love for each other and the props set up to keep them apart. Alex’s restrained but deliberate use of colour symbolises the new beginnings, possibilities and opportunities created by The Separation.

Glossary

Ngahere – forestAtua – god(s)

Manaia - a face in profile, with a bird-like beak

Hei tiki – pendant with a distinct humanoid shape

Puku – stomach

Other Artworks

Pou Tokomaunga

Kate Stevens West: Plywood, oil paints, steel tacks

Raki farewelled Papa and said to her “Remain here my darling. This is my love to you. In the eighth month I shall weep for you.” This is the dew, the tears of Raki weeping for Papa.

Then Raki said to his wife “My dear, live there. In the winter also shall I miss you.” This is the ice.

Tāne planted the trees. In the third year, the kahikatea tree bore fruit, and the birds of the heavens alighted on it.

Kate Stevens West began painting professionally in 2019 after starting her family of four children. Her work explores themes of whakapapa and time, and of whānau and tīpuna. Kate’s unique style suffuses Pou Tokomaunga with designs and patterns from the natural world, reminding us of our own connections to the whenua.

The central elements of Kate’s pou are the towering kahikatea, tall trees planted by Tāne to attract the birds held by his eldest brother Rehua. These birds are the source of language, they share their songs and help keep the forest alive. At the base of the pou are painted plants and flowers, inspired by the creations of Tāne but also representing Papatūānuku, the earth mother. Kate’s careful selection of colours such as the red-brown earth pigments of kokowai, reinforce the importance of Papatūānuku in the creation narrative. Rakinui, the sky father, is represented at the top cloaked with stars.

Surrounding and enveloping all is a reflective tōrino, a spiral of water in all its forms and the twisting emotions of Raki and Papatūānuku upon their separation. This tōrino is never-ending and conveys their endless love, longing and grief, and its envelopment of all things is a warning of all consuming love. It whispers the bittersweet sacrifices that parents make for their children – the consensual separation of Raki and Papatūānuku to let life-giving light into the world.

Glossary

Whakapapa – genealogyWhānau – family

Tīpuna – ancestors

Pou – post / pole

Whenua – land

Other Artworks

Te Tīmataka / The Beginning

Ariana Tikao with Paddy Free: Taoka puoro soundscape and waiata

This is the dew, the tears of Raki weeping for Papa. Then Raki said to his wife, to Papatuanuku, "My dear, live there. In the winter also I shall miss you."

This is the ice. And Papatuanuku farewelled Raki, and said to Raki, "My love, go, Raki. In the summer I shall greet you."

This is the mist, the love of Papatuanuku to Raki. Their final greetings ended, and Raki rose up through being lifted by Paia.

Ariana Tikao is an award-winning musician and author who is a New Zealand Arts Laureate. This audio work follows the narrative journey of darkness into light and the sounds of the atua Raki and Papatūānuku. The beginning of Matiaha Tiramōrehu’s manuscript says that in the darkness the atua began to sing:

Kei a te Pō te tīmatanga mai o te waiatatanga mai o te atua

The beginning of the singing of the Atua is with Te Pō (The Night)

The sounds present in our environment are emulated by taoka puoro, our ancestral instruments whose sounds connect us to atua, the many gods of different realms. The sounds of pūmotomoto, a flute, can be heard emerging from Te Pō, the darkness. Pūmotomoto are used during pregnancy and birthing.

The disruptive kōkiri sound made by the trumpet-like pūtātara signifies unrest and the need for change. The pūtātara consists of a conch shell and wooden mouthpiece, representing Takaroa, god of the seas, and Tāne, god of the forest. The breath used to play the pūtātara represents various atua of the winds. You will hear a rumble and a ripping sound as the sinews of Raki and Papa are stretched and severed. The sound of the pahū pounamu rings out with clarity and a sense of wonder as light floods this bright and spacious new world.

After Te Weheka, the separation, Raki and Papatūānuku exchange their grief and aroha, expressed in the form of falling rain and rising mist. Papatūānuku laments for her beloved who now lives far above her and out of reach.

The primordial parents still weep for each other. These tears are the continuing cycle of water that enables life on earth. Raki’s tears fall down to earth as rain, and Papatūānuku’s sighs of grief rise as vapour.

Here is the mist

my heart throbs with grief

here is the sadness, the aroha

The dew, the rain, are tears

from Rakinui, my heart’s desire

who stands apart from me, separated, my love

Obscured, hidden like a spirit

here I sit, yearning

so alone and bereft

We then move into the celestial realm, where Raki is adorned with stars and constellations, before the audio loops back to the beginning, symbolising the cycle of life.

Glossary

Atua – god(s)Pahu pounamu – greenstone gong

Aroha – love